Solo Episodes

This is intended as a guide for creating extended solo episodes as opposed to brief improvised sections that fit into a larger episode.

The jazz composer is a participant in the improvisation as much as the performers. The composer’s contribution consists of creating a structure for improvisation that is dynamic and helps advance the dramatic structure of both the solo episode and the composition as a whole. It should be noted that the improvisational structure includes the rhythmic as well as the harmonic/tonal structure.

Additionally, the composer also determines whether the improvisation happens occurs in a structured environment - written or partially written accompaniment such as an ostinato. Or, if the improvisation allows for free comping in the rhythm section. Hybrids are also possible.

In the past, backgrounds were often written for accompaniment purposes – especially in the era before electric amplification. In modern times, backgrounds are often a tool for the composer to influence the energy dynamic, development, and transitions in/around the solo episode. Using this tool allows the composer to integrate the solo episode into the entire composition in a more organic way.

Some Practical Suggestions

Areas of challenge (harmonically or rhythmically) should be offset by areas of ease. Good improvisers enjoy showing they can respond to difficult changes/meters. It’s always good to give them that chance. But it also will limit their improvisational vocabulary. If they’re responding to unusual/difficult harmonic structures, it means they are forced into “playing the changes.” If there are areas of simplicity in the solo form, they are able to include other ways of improvising. It’s also more musical to provide well placed variety.

Inner Urge by Joe Henderson is a great example of a song form that contrasts simplicity with challenge. For 16 bars of slowly shifting modalities the soloist can employ any number of improvisational approaches. The final 8 bars of rapidly shifting constant structures force the player into fewer approaches – some of which few listeners would perceive but are nevertheless impressive.

While it is useful to provide improvisers with areas of challenge, beware of areas of ultimate challenge. Complicated unfamiliar changes may be ignored players without the incentive to learn them. They may play what they want and justify it as playing “out.” Incentives to practice new complex progressions include a large enough paycheck, being recorded for release, a high visibility performance, or working with a well-known bandleader. If appropriate, use a challenging standard pattern like Coltrane’s three tonic cycle, the above-mentioned Joe Henderson progression, or a variant pattern.

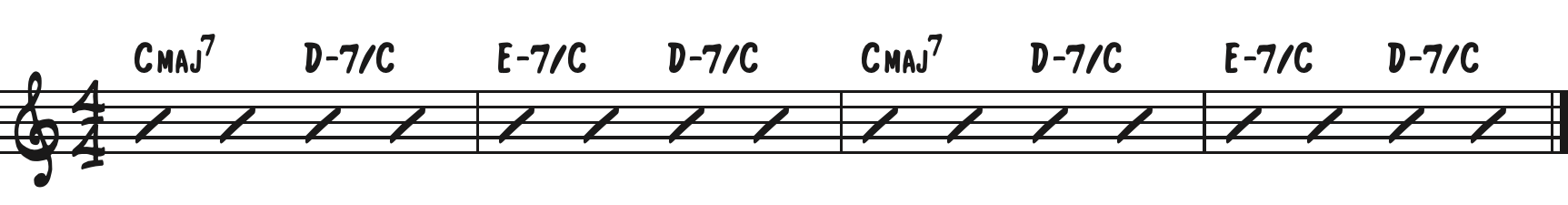

Sections of static harmony/modality allow the greatest freedom for players to improvise using most any technique they want. Areas of simplicity don’t necessarily have to sound simple though. Static harmony or modality can be animated. An animated simple pattern is still a simple pattern and is easily improvised on.

• Use a vamp, but disguise it by using alternate bass notes.

• Use simple diatonic patterns over a pedal.

• Modal patterns like dorian I-7, IV7 instead of static I-7 (Jobim’s Wave).

Or a spanish phrygian vamp instead of a static V7sus4 (Tyner’s Señor Carlos).

Use a variety of comping styles. Free comping - usually signified with slashes – allows for more communication. It has a loose open feeling to it. On the other end of the spectrum is heavily structured written comping, use of ostinato or prescribed rhythms that should not be changed. This challenges the improviser “ride the wave” of energy created by the accompaniment. The former can digress from the dramatic thread and not fit into the total composition as well. The latter can get tiring or boring if it goes just a little too long and can derail the energy curve the composer is trying to create. It is also possible to create a hybrid of the two comping approaches.

Maria Schneider does something similar with a constant structure mega voicing in the tune, Green Piece, at the beginning of the tenor sax solo. It’s used as an extended send off into an area of open free comping.

Create a solo episode that doesn’t remain static for too long. By employing some creative contrast, you give the players a dynamic vehicle on which to improvise.

· Contrast sections of groove with sections of kicks and breaks.

· Use multiple sections with contrasting grooves.

· Use multiple sections with contrasting comping approaches.

· Use backgrounds to influence the energy curve. They can also enhance kicks and breaks.

Create a solo episode with a well thought out dramatic structure. What is the energy curve intended to be?

· Plan the moments of repose and climax.

· Start big, come down, build back up.

· Start with a break down and gradually build to climax.

· Where is the climax of the episode?

o Climax can be in the transition (or exposition) following the end of the solo.

o Climax can be right at the end of the solo, following transition/exposition relaxes.

o Climax can be near the end but allows for relaxation before ending.

· Backgrounds are a big influence on the dramatic structure

o Starting with unobtrusive backgrounds and gradually rising into the foreground will have a more subtle affect – at least until they break into the foreground.

o Backgrounds that enter big and suddenly will be explosive.

o Backgrounds supporting kicks and breaks will enhance their affect.

Approaches to Improvisation

Being aware of organizational techniques used by improvisers can also help the composer create dynamic, fun to play solo episodes. Here is a partial list of techniques. It should be noted that many of these techniques can be combined.

· Key Area: just playing in the key without marking harmonic movement.

· Chord Tone Solo: using only chord tones and voice leading as a way of articulating the harmony.

· Chord Tones plus Tensions: same as chord tone solo but including chord tensions.

· Chord Scale: utilizing non-harmonic approach notes.

· Playing the Changes: specifically outlining the harmony, maybe including some simple reharmonizations, be-bop patterns and phrasing.

· Extended Chromaticism: areas of chromatic motion that are not always aligned with the given harmony

· Motivic Development: working motivic ideas through the harmony, giving melodic continuity more importance.

· Quoting Familiar Melodic Phrases or Other Tunes

· Pattern Playing: using a motif or arpeggio/scale pattern to take a thematic thread outside the given harmony

· Triadic Patterns: using triads as the building block for pattern playing. Can be used while staying inside or outside the given harmony.

o Lower Structure Triads

o Upper Structure Triads

o Non-Harmonic Triads

· Pentatonic Patterns: similar to triadic patterns but using pentatonic scales. Can be used while staying inside or outside the given harmony.

· Superimposing Foreign Chords: over a given harmony.

· Superimposing Foreign Keys: over a give key area.

· Superimposing Polyrhythms: use of patterns of 5 is currently quite popular. Listen to drummers.

· Superimposing Polymeters: for example, groupings of triplets. Listen to drummers.

· Variations of Rhythmic Density

· Variations of Dynamics, Articulation, Swing

· Variations of Approach: see above